Shining a Light on Region’s Deep-Sea Corals

Twenty thousand years ago, the vast underwater plain we know as the Mid-Atlantic’s continental shelf was dry land and the region’s beaches were 100 miles east of where they are today, near the current shelf break. Where pre-historic rivers met the sea, the force of their flow, along with scour and erosion, cut through the rocks and seafloor, chiseling out dozens of Grand Canyon-like formations in their place.

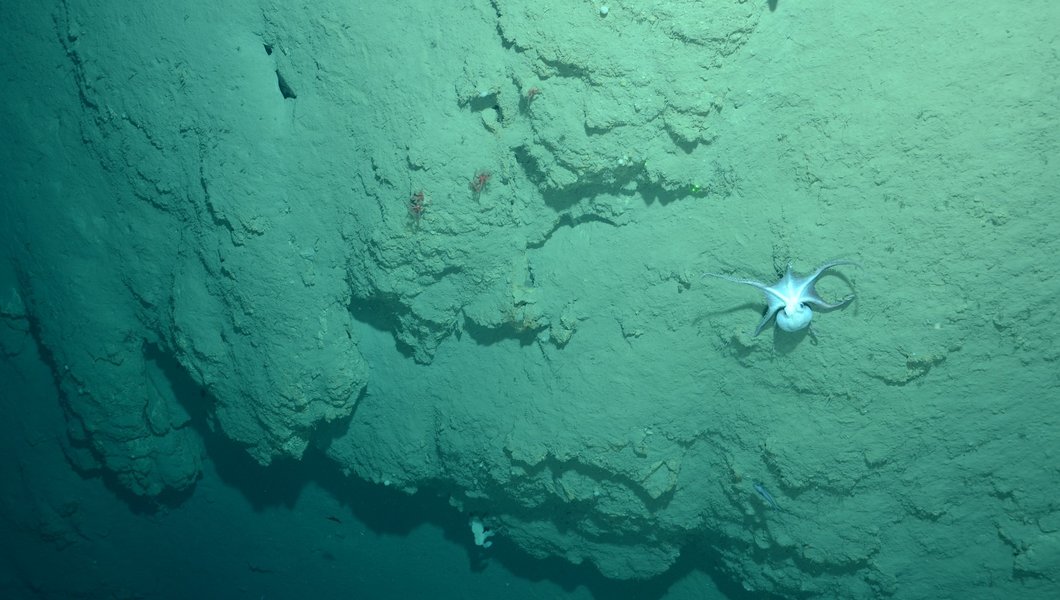

But as the Ice Age waned, an ocean of land-locked water in the form of mountainous glaciers melted, burying the shelf and the canyons 100 fathoms beneath the waves. Those canyons and the colorful cast of life forms inhabiting them have since remained far out of human view – until now.

Dr. Timothy Shank, a biologist with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), is among a team of researchers led by chief scientist Dr. Martha Nizinski (NOAA Fisheries zoologist) along with WHOI biologist Taylor Heyl who explored eight of the Mid-Atlantic’s lesser-studied canyons in two recent summers. With the aid of towed camera technology, Shank and the team have revealed what the insides of these ancient formations look like in stunning detail and mapped the locations of thousands of never-seen coral colonies.

“It hit me quite hard when I realized, this is underwater America,” Shank said. “These canyons are our property just like Manhattan is or Los Angeles is. Almost half of America is underwater.”

The more than 110,000 images gathered in his expeditions helped inform the process that led to the creation of the Frank R. Lautenberg Deep-Sea Coral Protection Area (shown in above map), which placed roughly 38,000 square miles of federal waters off the Mid-Atlantic coast off limits to bottom-tending fishing gear. Shank’s work was supported with grant funding from the Mid-Atlantic Regional Council on the Ocean (MARCO) and conducted aboard the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) FSV Henry Bigelow.

In this Ocean Stories feature, Shank shares memories and images from each of his stops, from north to south: the Ryan, Carteret, Lindenkohl, Spencer, Washington, Wilmington, Leonard and Accomac canyons.

Ryan Canyon

The northernmost canyon studied was Ryan, a narrow formation located roughly 90 miles from New York’s Hamptons. Ryan runs closely parallel to a near twin in McMaster Canyon, and the two connect after about 20 miles.

“Ryan has a distinct morphology,” Shank said. “It goes deep quickly and sort of stays deep, without a lot of twists or turns.”

Ryan also stood out to Shank for a heavily sedimented bottom that ran nearly the full extent of the canyon. In comparison, he said most canyons are rocky at the openings, then fluctuate between softer and harder environments as they descend. The consistent hard-bottom environment made a good habitat for hard cup corals and soft bamboo corals, but did not support as diverse number of species as many of the others.

Carteret Canyon

Fifty miles south of the legendary Hudson Canyon is the far smaller Carteret, the namesake of Philip Carteret, who in 1665 served as the first governor of New Jersey. It is one of a tight cluster of small formations off the Jersey coast that fishermen refer to colloquially as “the Finger Canyons.”

Several sponges and some black corals were located within the Carteret. Shank recalls the canyon’s steep vertical walls and high population of fishes as being distinct features. He described one scene with an especially thick congregation of cutthroat eels above the lip of the canyon as looking like “a party on the wall.”

Lindenkohl Canyon

Carteret’s neighbor just seven miles to the south is the Lindenkohl Canyon. While not massive in size, Shank described it as pound-for-pound being home to perhaps the most diverse and abundant population of marine life in the Mid-Atlantic.

Within its stretch he saw many species of black corals, hard corals, soft corals, sea pens and sponges, some of which were exclusively found there. Crabs, shrimp, octopus and brittle stars were also high numbers. Yet one thing that stood out was the near absence of corals in its shallower areas, which are usually well populated.

“Every time we were in the head of a canyon you’d see sea pens, because they love the sediment,” he said. “So to find none in the shallow areas made us wonder, why is that? It’s an interesting pattern we hadn’t seen before.”

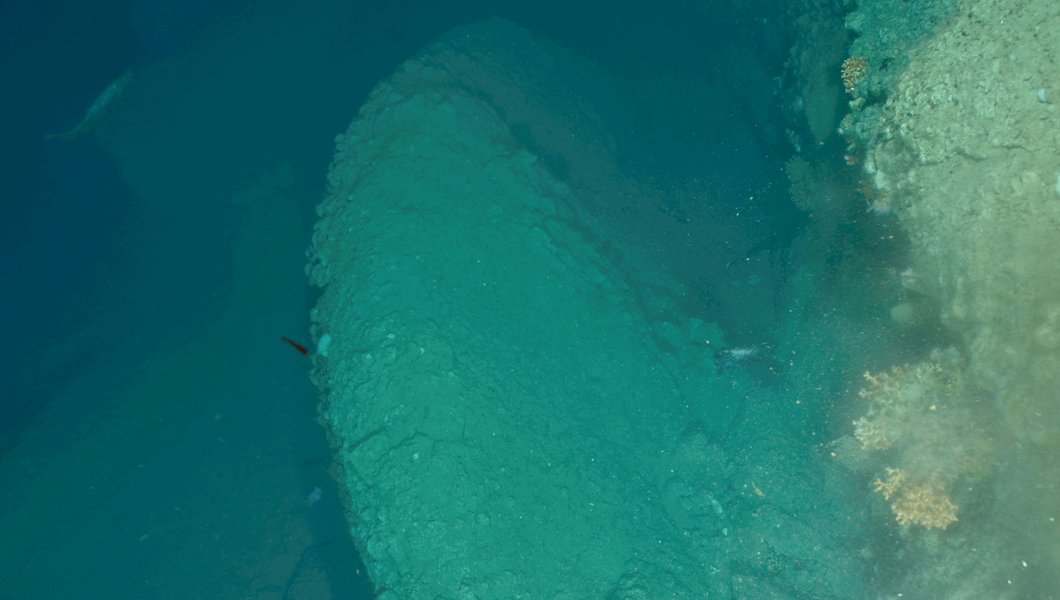

There were also many fish species dominating the walls of Lindenkohl at about 800 meters deep.

“There were skates everywhere,” Shank recalled. “It was loaded. That’s the only canyon that we ever saw skates in really high abundance.”

Spencer Canyon

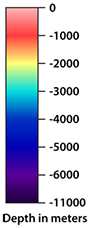

Like Atlantic City 80 miles to its west, the Spencer Canyon is a place going through plenty of redevelopment these days. Shank recalls Spencer as being rife with signs of “mass waste” – essentially piles of rocks and sediment near the canyon walls where underwater rockslides occurred.

These mass wastes can crush coral colonies that have been growing for thousands of years. But the disasters also create conditions on the sea floor where marine life will thrive in the future. Shank said he’d love to return to Spencer in a few years to revisit these sites and see whether life has returned.

“These canyons are organic – it’s almost like they are alive,” Shank said. “You can be looking at a canyon wall loaded with diverse corals living on it. Then you move down a few meters and you’ll see a place that’s totally bare of any corals, sponges or anything else. You can see that the wall recently mass-wasted face – the whole face of the canyon wall collapsed and went downslope just like ice sheets calving into the ocean. I remember Spencer having that dynamic morphology. It must impart where corals live.”

Wilmington Canyon

The largest, longest and deepest of the canyons examined was the Wilmington, located 80 miles off Rehoboth Beach, Delaware. Shank said Wilmington’s black corals appeared to be very similar to the ones observed in Spencer Canyon 18 miles to its north, with a key difference: Wilmington’s corals were scarce in the shallower depths near the mouth of the canyon. For Shank, this raised a host of scientific questions about genetics and currents in the region.

“What I want to do now science-wise is look at the genetics of the black corals to tell whether the ones in Wilmington and Spencer are communicating – if they’re connecting genetically,” he said. “If they’re divergent in their genetic composition, it tells me the canyon environments may be acting to isolate those populations of black corals from each other and through evolutionary time, become different species.”

With DNA samples from the various canyons, scientists could determine which canyons are true hubs of diversity rather than places where larvae simply land and colonize, he said. Such information could help agencies in ocean management roles determine whether the hub areas should receive specific kinds of marine protections.

Leonard and Accomac Canyons

Some 60 miles from Ocean City, Maryland, are the sister canyons of Leonard (to the north) and Accomac. The upper edges of the two canyons run as close as a half-mile from each other at points, and converge after less than 15 miles.

It’s therefore no surprise that Leonard and Accomac would share very similar compositions of marine life. Mushroom corals, sea pens and a small number of black corals were seen in the canyons.

“There’s a little side saddle between them,” Shank said of a seam that connects the two formations a few miles in. “There could be more larvae exchange between them than the other canyons, which may explain how biologically similar they are.”

Washington Canyon

The final stop on Shank’s expedition was the Washington Canyon, about 30 miles south of the Accomac. The canyon had heavy sedimentation at its head, steep walls, rocky benches and plenty of shards of fallen rocks in its deeper reaches.

“Because you had all those different habitats, you had many different corals,” Shank said. I think that’s why we saw such diversity in Washington Canyon.”

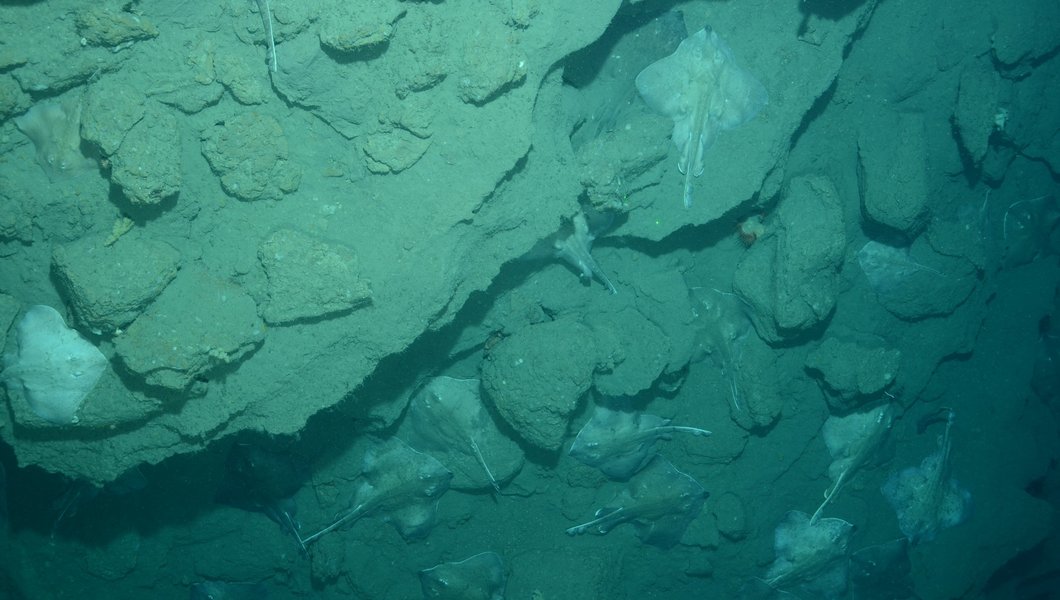

A standout feature of Washington Canyon was the many cracks along its walls, which made ideal spots for larvae to settle and grow.

“It looks like coral curtain rods – long lines of corals in a row, all competing for space in those cracks,” Shank said. “Coral diversity [between 1000 and 2000 meters] was the highest we observed of all of the Mid-Atlantic canyons.”

For More on this Research

- MARCO and WHOI hosted a webinar featuring Dr. Shank's work titled The Underwater United States

- Gallery of images from the canyon expeditions

- Dr. Shank shared more findings from his expeditions in a report titled “Deep-water coral and fish of U.S. Mid-Atlantic Canyons.”

- Download zip file containing spreadsheets with points data for coral observations

- MARCO also produced this educational story map focused on the Baltimore, Hudson and Norfolk canyons.

Story by: Karl Vilacoba, Monmouth University Urban Coast Institute. He can be reached at kvilacob@monmouth.edu.

Support for this Research

The data collection at sea and initial data analysis was supported by the NOAA Deep-Sea Coral Research and Technology Program, with project partner Martha Nizinski, NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service. Data analyses was supported by MARCO with project partners Brian Kinlan and Matt Poti. Sea-going technical support was provided by WHOI's MISO Facility.